Dead by Daylight:

Proscribed Emotional Learning and Vulnerability through Horror

“The oldest and strongest emotion of mankind is fear, and the oldest and strongest kind of fear is fear of the unknown.”

— H.P. Lovecraft

“We have to work as a team, I need you to survive so that I can survive!”

— Dwight Fairfield

Introduction

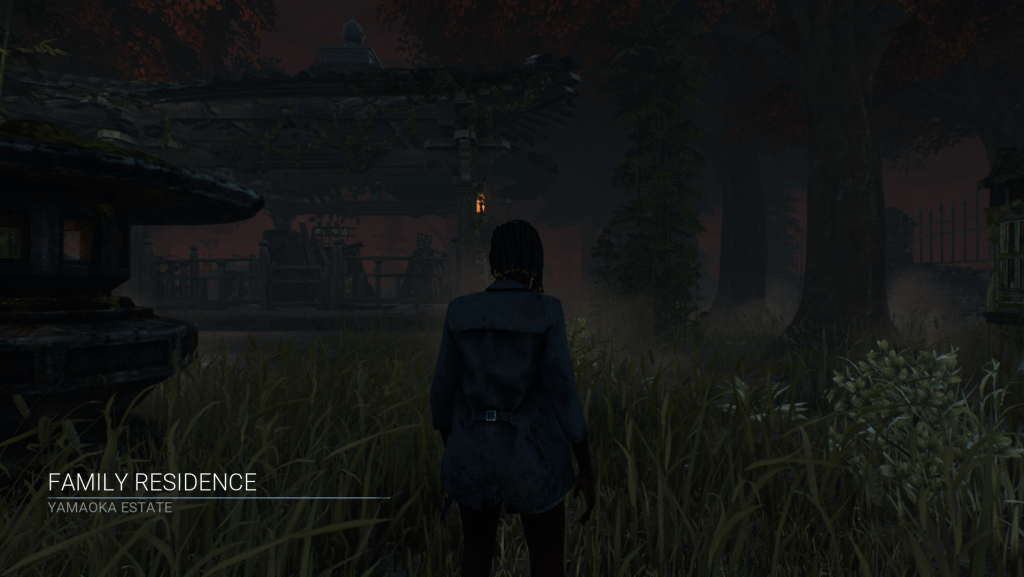

The game chosen for this analysis is an asymmetrical horror game I frequent called Dead by Daylight. I boast a playtime of 469.7 hours – many of which is with the same two friends (see Appendix, figure 1). Dead by Daylight was chosen for its unique stance in asymmetrical horror games (as among the top) as well as the fascinating implications horror videogames can have on “education” and “good learning”. The pedagogical capacity for horror games, specifically Dead by Daylight, fulfills the ability for one to ‘emotionally’ learn, and connect with oneself. Further, in the game being couched in horror, the player’s teamwork decisions are layered with nervousness – making the decisions that much more intense. Fear, in this context, can be mobilized toward a deeper understanding of oneself and others, as well as environments and mechanics of the game.

Game Overview

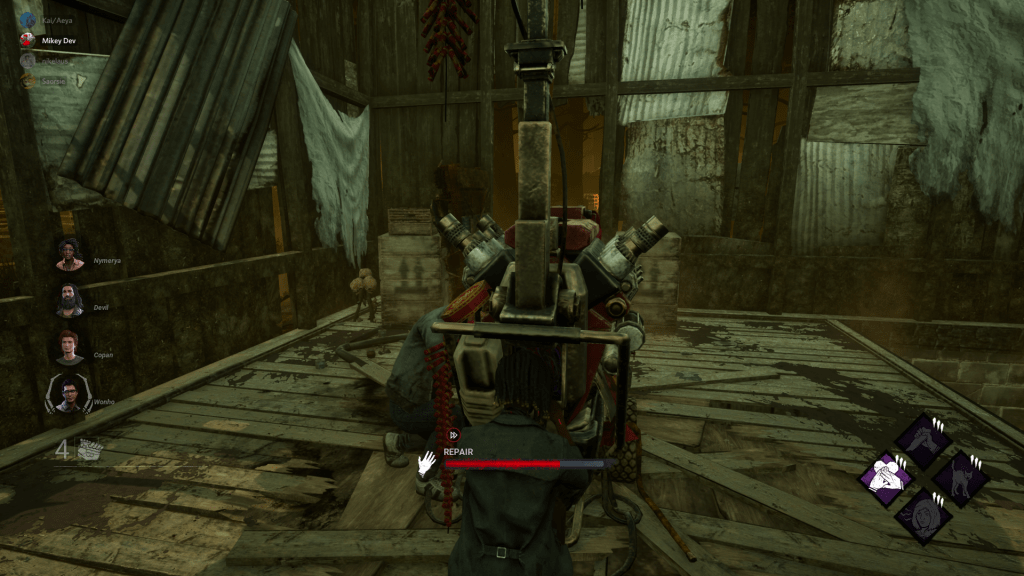

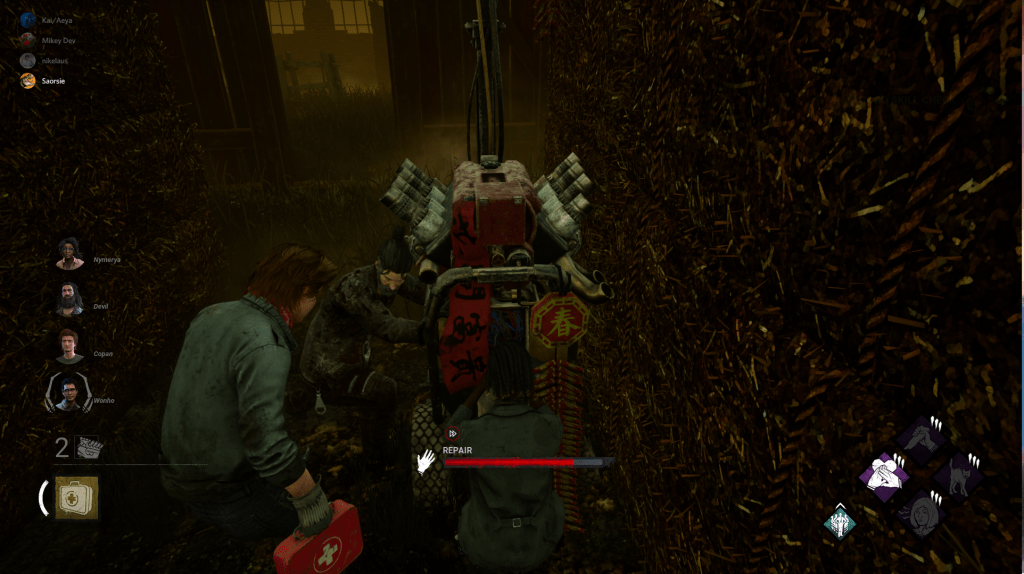

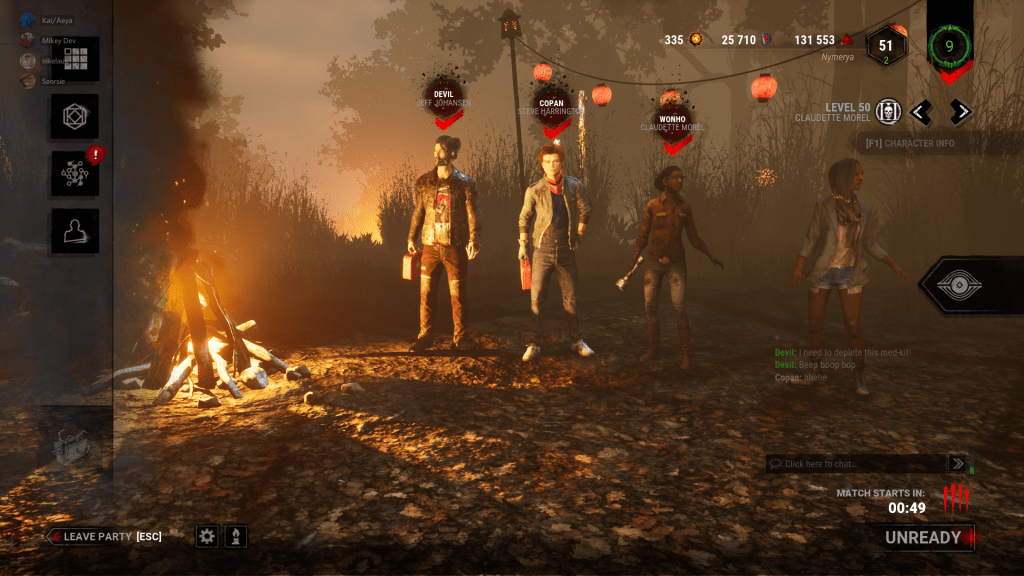

Dead by Daylight requires five players and is played completely online (no LAN capabilities). The players choose between a survivor or killer. Each choice has different perks and abilities. The survivors cannot harm the killer – instead, their main goal is to completely repair five generators (of which there are seven scattered across the map). Once (if) completed, the survivors must open one of two doors to escape the killer and “win”. The killer, in tandem, must try to find the survivors and “hook” them. The survivor can withstand two hooks – on the third, they die and ‘lose’ the game. There are, of course, many more detailed mechanics which make the game have amazing re-playability. An interesting mechanic is that players can only talk to each other in the ‘lobby’ before the game. Otherwise, they must rely on clothing, character appearance, and gestures to communicate (unless, of course, you are a SWF [surviving with friends] group and talk on another platform).

Establishing Horror Games’ Abilities in Education

Though horror games, themselves, appear to be a site for emotion-based drives (fear, panic), they are, simultaneously, captivating spaces of emotional depth, conceptual action, and ‘safe’ experience. Playing the game, itself, invokes within the player a sense of urgency, fear, and nervousness. Noël Carroll, a foundational horror philosopher, asserts a distinction between “natural horror” and “art horror” (1990, p. 13); Carroll further claims “[t]hat monsters are a mark of horror is a useful insight” (1990, p. 14). Dead by Daylight, then, is a curious game as it relies on many previously established horror elements – having implemented well-known killers from popular movies and TV shows: Stranger Things, Nightmare on Elm Street, Halloween, etc. As such, the “category” of Dead by Daylight is complicated yet, patently, artistic horror. Horror, itself, is couched in elements of psychological and existential dread. To learn through a horror game, then, is to come to terms with one’s own reality, emotions, and perspective.

Lysgaard, Bengsson, and Laugesen, in their book Dark Pedagogy, outline the ways in which horror can underscore education in its relational abilities; they write:

“humans are vulnerably suspended in a world where cosmically odd powers far greater than the frail efforts of human beings control and condition how the world is unravelling and strange and inexplicable events take place with often times disturbingly detrimental, mind-twisting and insanity inducing consequences for the human beings involved in the maelstrom of the nonhuman” (2019, p. 5).

Horror videogames are a mirror of this space of human versus nonhuman “maelstrom”. Lysgaard, Bengsson, and Laugesen later discuss how the very essence of ‘vulnerability’ can outline a form of self-realization pedagogy. Horror videogames are a sublime site of vulnerability – one that requires the player to render their own approach to the objects in the game as well as to themselves.

Relation to Educational Simulations and Learning

Having established the ability of horror games to invoke a deeper sense of existentialism and emotion, this section will discuss the various ways in which Dead by Daylight can be experienced as a ‘learning’ game. Specifically, this section will explore James Gee’s work on videogames as being “good” for learning in reference to Dead by Daylight.

The system of Dead by Daylight encourages as process of interacting with simulation(s) which evoke our deepest sense of dread and existentialism. Often, the opportunity to explore one’s darkest emotions in reference to education is uncommonly encouraged. Here, the game can be seen through Gee’s second game feature: “simulations of experience and preparations for action”. As Gee asserts, “Video games are external (not theoretical) simulations of worlds or problem spaces in which the player. using a particular perspective, must prepare for action and the accomplishment of goals” (2006, p. 4). Horror videogames offer a site of unique and ‘safe’ existentialism. A player enters the game knowing that the simulated world will be uncanny; the player must, then, work to strip down their expectations and learn their new reality. In this learning (encountering) of the abject world, the player reverts to their most basic instincts: fear, reaction, empathy. Do you help your fellow player off the hook? If you do, the killer will be notified and might come for you. Do you hide the whole game and not risk helping with generators? Do you experiment with ‘bravery’?

Indeed, in relation to the ‘teammates’ function of Dead by Daylight, each player is crucial to the game mechanics and learning capabilities. This affiliation fits neatly under Gee’s concept of “cross-functional teamwork” (2006, p. 5). Gee emphasizes the ability for players to “organise around a primary affiliation to their common goals and use their cultural and social differences as strategic resources, not as barriers” (2006, p. 5). This dynamic of cultural, racial, and/or social differences is embodied in an extraordinarily noteworthy way in Dead by Daylight. To be the characters who are darker skinned is, at its heart, an advantage in the game. The more one can blend in with the dismal (and dark) surroundings, the more they will be able to ‘hide’ from the killer. As such, the characters with blonde hair, bright clothes, and white skin are disadvantageous (unless of course the player is a ‘looper’ [one who aggros the killer and tries to keep their attention]). The game, here, draws on race as an ‘advantage’ to the game mechanics. As well, the choice of character, clothing, and play style signals to other players what type of player they will be on the team.

The killer in this game “The Doctor” was stymied by us the entire game. At the end, he ‘gave up’ and just stood there so all four of us ‘crouched’ in front of him to ‘tell’ him “it was okay’.

Similarly, the network of players in the game work well in what Vittorio Marone calls “affinity spaces” (2016, p. 10). For the social environment to flourish, ‘competence’ of the game expectations and mechanics is crucial. Most of these processes are learned only through one engaging with the game and with other players and killers. Indeed, Marone, citing Jonassen and Land, submits: “By engaging in these social-constructive endeavors learners ‘absorb part of the culture that is an integral part of the community, just as the culture is affected by each of its members (Jonassen & Land, 2000, p. vi)” (Marone, 2016, p. 10). In order to accrue knowledge of the game mechanics, players (much like Marx’s base and superstructure) inform each other. New “metas”, skills, and “positions” (looper, gen-jockey, etc.) are updated and assigned as players learn the intimate details of the game’s abilities.

Dead by Daylight is a massively “silent” game in that there is very little dialogue, and all “words” are saved for game lobbies. What comes in place of this, then, is gestures and experience. Under Gee’s notion of “situated meaning”, the experience of Dead by Daylight boasts a complex and exploratory understanding (2006, p. 6). Indeed, Gee writes: “[s]ince video games are simulations of experience, they can put language into the context of dialogue, experience, images and actions” (2006, p. 6). In understanding the complex system of gestures and movements in Dead by Daylight, one learns to attune and “listen” with more than language. Since players are coded by their clothing, skin colour, and demeanor, a “Claudette” (POC woman known for ‘stealth’ and gen-jockeying) is assumed to have a skill called “Spine Chill”. This ability lights up an icon for the player to see whenever a killer is within certain range. As such, a teammate working on a generator with a Claudette learns to pay attention to the Claudette’s actions: is she suddenly leaving the generator? Is she running (the killer is close)? Is she crouched (there is time to hide)? As such, a player must learn the nuanced system of language within the game – and develop a hyper-aware alertness for a variety of variables: their own emotions, other players, the game itself, and their environment.

Similar to the first clip, the “Nurse” in this game tried to outsmart us by ‘teleporting’ to the exit gates. She got stuck so this is us ‘making fun of her’.

Finally, Gee’s notion of “empathy for a complex system” is relational to the generator placement and teamwork function of the game (2006, p. 2). As there are seven generators on the map, and the team must complete five, the team must be cognizant that they do not “three gen” themselves wherein the last three generators that need to be completed are within close proximity. If the team is “three gen’ed”, the killer has end-game advantage and players did not coordinate well with their other teammates to space out generators. This patterning is crucial to the game and multi-layered in its actuality. A player might be too ‘scared’ to complete a very exposed generator, they might not be playing well as a team, or the killer might be “patrolling” specific generators more frequently. In the first instance, here, a player’s fear is foremost before teamwork. However, the player will quickly realize that they cannot let their fear control them or they will never win the game(s). As Gee discusses, in relation to scientists describing phenomena and simulations: “they aim to gain a deeper feel for how variables are interacting within the system” (2006, p. 2). A player, then, in Dead by Daylight, must learn and respect the system of the game. They must intimately understand the mapping system, learn to scope out which generators to work on, and when to move past their own fear(s).

Conclusion

The way in which one “learns” in Dead by Daylight is nuanced and atypical of classic learning experiences through games. Indeed, learning in horror games is layered with emotion; and, overcoming that emotion (usually fear) is paramount to conquering the game, itself. “Good learning”, then, intertwines emotion and learning into a seamless aesthetic ‘problem’ that, when overcome, is motivating and effective at obfuscating ‘boring’ methods of play. Dead by Daylight is excellent at providing digital strategy in tandem with teamwork – all the while with an emotional layer troubling the player. A good game must be carefully thought through, have room for improvement of skills, and be comfortably complex. In the evocation of fear as an emotion, the game allows for education in a non-traditional sense: one which utilizes revulsion, disgust, and enjoyment all at once.

Works Cited

Carroll, Noël. (1990). The Philosophy of Horror or Paradoxes of the Heart. Routledge, New York: NY. Print.

Gee, James Paul. (2006). Are Video Games Good for Learning? [Conference Keynote Presentation]. Curriculum Corporation 13th National Conference, Adelaide, Australia. http://www.curriculum.edu.au/verve/_resources/Gee_Paper.pdf

Lysgaard, Jonas Andreasen, Stefan Bengsson, and Martin Hauberg-Lund Laugesen. (2019). Dark Pedagogy: Education, Horror and the Anthropocene. Palgrave Macmillan, Cham: Switzerland. Print. Marone, Vittorio. (2016). “Playful Constructivism: Making Sense of Digital Games for Learning and Creativity Through Play, Design, and Participation.” Journal of Virtual Worlds Research, Vol. 9(3).

Marone, Vittorio. (2016). “Playful Constructivism: Making Sense of Digital Games for Learning and Creativity Through Play, Design, and Participation.” Journal of Virtual Worlds Research, Vol. 9(3).

Appendix

Figure 1: A (notable?) demonstration of my commitment to the game.